The Evil Dead might have been an unexpected film to watch on Christmas day, but we went ahead and did it anyway. In some flippant way, zombies actually fit rather nicely into the Christmas tradition. Okay, so maybe Dawn of the Dead (in which humanity makes its last stand in a shopping mall) would have been slightly more appropriate. But that's not the movie my sister got for Christmas.

The Evil Dead might have been an unexpected film to watch on Christmas day, but we went ahead and did it anyway. In some flippant way, zombies actually fit rather nicely into the Christmas tradition. Okay, so maybe Dawn of the Dead (in which humanity makes its last stand in a shopping mall) would have been slightly more appropriate. But that's not the movie my sister got for Christmas.

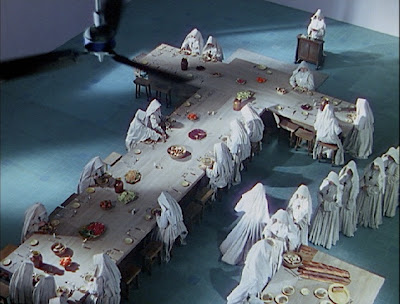

What surprised me a little bit about this film is how basic the plot is. Although, Sam Raimi may have set the archetype for this type of isolation-bad-things-ensue horror movie, I'm not sure about that. Certainly, he was one of the first to achieve something this formally brilliant with such a tiny budget (in the area of 300,000 dollars, I believe). The plot is this: a group of five young people set off to spend the weekend in a cabin together (But how did they get it so cheap, anyway?). Upon getting there, they accidentally arouse the spirits of the dead, who inhabit and kill them each in turn, barring their exit by knocking down the one rickety bridge that would allow their egress. That's pretty much all there is to it, but Raimi's use of the camera and his ability to create tension make this film amazing and incredibly frightening, even to a Saw-jaded viewer, such as myself. This film might even be a precursor to gross-out horror, as the one way to get rid of the zombies is by total dismemberment, which we get to witness every part of!

The gender politics are strange, as well. It is a mistake that the first girl to fall prey to possession by the evil spirits is the one girl who came without a boyfriend? I think not. She is essentially raped by the forest, and soon becomes rampantly possessed. Ironically, she is the last zombie standing in the end, and the one that almost does Ashley (Bruce Campbell) in. The next two to succumb are the girlfriends of the two men. In various ways, each are inevitably destroyed by their boyfriends. In some fierce perversion of the femme fatale, the women in this movie become the evil force that must be overcome. And this can only be achieved by total, grotesque bodily annihilation.

The gender politics are strange, as well. It is a mistake that the first girl to fall prey to possession by the evil spirits is the one girl who came without a boyfriend? I think not. She is essentially raped by the forest, and soon becomes rampantly possessed. Ironically, she is the last zombie standing in the end, and the one that almost does Ashley (Bruce Campbell) in. The next two to succumb are the girlfriends of the two men. In various ways, each are inevitably destroyed by their boyfriends. In some fierce perversion of the femme fatale, the women in this movie become the evil force that must be overcome. And this can only be achieved by total, grotesque bodily annihilation.

If you as unnerved as I was at the end of this movie, watch the outtakes. Taken out of context, the scenes of goop and growling are hilarious. Stripped of the veneer created by editing, the constituent scenes of this movie really reveal its shoestring budget. This just makes it seem all the more amazing that Raimi managed to create the horror masterpiece that he did.

If you as unnerved as I was at the end of this movie, watch the outtakes. Taken out of context, the scenes of goop and growling are hilarious. Stripped of the veneer created by editing, the constituent scenes of this movie really reveal its shoestring budget. This just makes it seem all the more amazing that Raimi managed to create the horror masterpiece that he did.