In Black Narcissus, a group of nuns, headed by Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) are sent to the Himalayas to start a school. As Criterion states it, the film is a "fascinating study of the age-old conflict between the spirit and the flesh," which is, naturally, simplifying things a bit. It is true, though, that the premise encourages the audience to think directly along those lines as the hard-edged spiritual nuns are thrown headlong into a den of hedonistic sin, led by Mr. Dean (David Farrar). The new environment incites a deeply personal struggle for each of them. Black Narcissus surprised me. I was expecting something more dark. It was, at parts, but more often, it was playful and dreamy. Although the whole set-up is pretty surreal, it really seems to touch on something inherently human, although it is hard to describe exactly how. Through its dream walk atmosphere, the film explores a constant battle within ourselves between what we want ourselves to be, and what we are.

In Black Narcissus, a group of nuns, headed by Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) are sent to the Himalayas to start a school. As Criterion states it, the film is a "fascinating study of the age-old conflict between the spirit and the flesh," which is, naturally, simplifying things a bit. It is true, though, that the premise encourages the audience to think directly along those lines as the hard-edged spiritual nuns are thrown headlong into a den of hedonistic sin, led by Mr. Dean (David Farrar). The new environment incites a deeply personal struggle for each of them. Black Narcissus surprised me. I was expecting something more dark. It was, at parts, but more often, it was playful and dreamy. Although the whole set-up is pretty surreal, it really seems to touch on something inherently human, although it is hard to describe exactly how. Through its dream walk atmosphere, the film explores a constant battle within ourselves between what we want ourselves to be, and what we are. There's some imperialism thrown into the mix, as well, which i don't feel entirely equipped to deal with. In a manner that is reminiscent of the jungle in Heart of Darkness, it is the very atmosphere of the place that seems to drive the inhabitants to madness. For the most part, the treatment of the natives is similar, too. With several exceptions, they are presented en mass, always on the periphery. Simultaneously, they seem to be at the center of the narrative and outside of it.

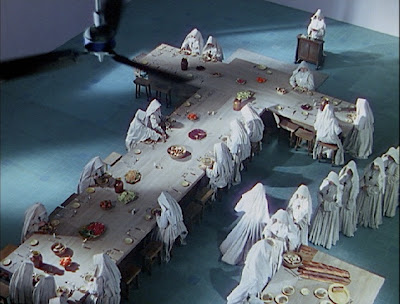

There's some imperialism thrown into the mix, as well, which i don't feel entirely equipped to deal with. In a manner that is reminiscent of the jungle in Heart of Darkness, it is the very atmosphere of the place that seems to drive the inhabitants to madness. For the most part, the treatment of the natives is similar, too. With several exceptions, they are presented en mass, always on the periphery. Simultaneously, they seem to be at the center of the narrative and outside of it. In a stark building, perched on top of desolate mountains, surrounded by drumming natives, the nuns attempt to do their work. The imagery on top of the mountains suggests something between Eden and Mount Olympus, but it is made ominous by frequent, exaggerated high angles, which show the land below disappearing into fog. Often, the place seems to be outside of reality. It is totally isolated, and the wind is constantly blowing with a steady drone underneath the action, causing the nun's habits to be in constant motion. The Saris of the natives, particularly the sultry Kanchi (Jean Simmons) move in a similar way as if drawing a comparison between these polar opposites.

In a stark building, perched on top of desolate mountains, surrounded by drumming natives, the nuns attempt to do their work. The imagery on top of the mountains suggests something between Eden and Mount Olympus, but it is made ominous by frequent, exaggerated high angles, which show the land below disappearing into fog. Often, the place seems to be outside of reality. It is totally isolated, and the wind is constantly blowing with a steady drone underneath the action, causing the nun's habits to be in constant motion. The Saris of the natives, particularly the sultry Kanchi (Jean Simmons) move in a similar way as if drawing a comparison between these polar opposites. In one of my favorite scenes, Sister Clodagh confronts Sister Briony (Judith Furse) about her waning spirituality. Briony is troubled by the atmosphere; she can see too far. It causes her to forget why she is planting potatoes, and then to question why she is doing it at all. I especially like this reflection on the space of the place; it's like the environment reflects or causes a void to open within the characters. Later, Con (Shaun Noble) teaches the Indian children English by marching them around the gardens, chanting the words for the objects they see. The almost musical rhythm of various flower names inter-cut with Sister Clodagh, who, while listening discovers that Sister Briony has indeed abandoned her potato planting, and has diverged totally from the strict plot of vegetables she was assigned. She rejects true sustenance for a kind of soul-sustenance. The same disintegration occurs in all of the nuns, including Clodagh, herself, who becomes plagued by memories of her past.

In one of my favorite scenes, Sister Clodagh confronts Sister Briony (Judith Furse) about her waning spirituality. Briony is troubled by the atmosphere; she can see too far. It causes her to forget why she is planting potatoes, and then to question why she is doing it at all. I especially like this reflection on the space of the place; it's like the environment reflects or causes a void to open within the characters. Later, Con (Shaun Noble) teaches the Indian children English by marching them around the gardens, chanting the words for the objects they see. The almost musical rhythm of various flower names inter-cut with Sister Clodagh, who, while listening discovers that Sister Briony has indeed abandoned her potato planting, and has diverged totally from the strict plot of vegetables she was assigned. She rejects true sustenance for a kind of soul-sustenance. The same disintegration occurs in all of the nuns, including Clodagh, herself, who becomes plagued by memories of her past.Most striking is the descent of Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron) into psycho-sexual madness. This can only really be described in images:

This is a haunting film, and I keep finding myself running certain scenes over and over in my mind. To say that this is just a parable about sexual repression would be far too reductive. Black Narcissus is the kind of film that is almost too good for this kind of analysis. It leaves you with something you can't explain; you have to just see it for yourself.

This is a haunting film, and I keep finding myself running certain scenes over and over in my mind. To say that this is just a parable about sexual repression would be far too reductive. Black Narcissus is the kind of film that is almost too good for this kind of analysis. It leaves you with something you can't explain; you have to just see it for yourself.