Sunday, March 28, 2010

Alphaville, une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution

I'm going to hurriedly scribble some thoughts on this one. It's been a few weeks since I saw this now, and I've got a backlog of films, most of which will not make it on here. Anyway. I don't remember how I discovered the existence of this movie, but as soon as I learned of this Godard-directed, pastichey sci-fi noir, I leaped upon it immediately, like a moth to the proverbial flame! In a traditional sense, it is very noirish indeed. Godard makes something out of almost nothing, by which I mean, the budget. Most of the scenes are indoors, and except for some flashing lights and machinery, Alphaville could be any city, anywhere. Much of it could have been filmed in someone's basement or high school hallways.

Labels:

1965,

Anna Karina,

French New Wave,

Jean-Luc Godard,

noir,

sci-fi

Tuesday, March 9, 2010

The White Ribbon

I'll make this one relatively brief, mostly because it's so hard to know where to begin. Watching Haneke's films I always feel like I'm being taunted by a being whose intelligence is far greater than my own. His films are incredibly open ended, leaving some viewers claiming that there are no answers, while some claim with positivity that they know just what he was aiming for (check out the imdb boards). To me, Haneke is brilliant. He's the only director I can think of who is a master of visually storytelling, yet manages to make a movie, purposefully eliminating what other filmmakers would consider key scenes, only to have the film turn out better for it. In the White Ribbon, there is a masterful play of show and tell. Haneke makes choices that might be completely wrong in the hands of someone less capable.

Haneke manages to straddle some elusive barrier between subtlety of message and overtness. I mean, it's a morality play shot in high contrast black and white; that's pretty blatant metaphor. Also, it deals with the oppressed children in a German rural township who will grow up to be the Nazi generation. Yet, there's a profound deepness to his work, and i think it somehow hearkens back to what he chooses to show and what he doesn't. He doesn't condescend to his audience by handing them the answers on a platter. His films reflect a world where there are no easy answers.The movie depicts a period of time, about a year in length, in which a serious of increasingly violent crimes are committed. Almost every single one happens off screen; we only see some of the aftermath--a body, a boy crying. Rather than cutting within the scene, Haneke tends to position the camera, then having his subjects walk in and out of the frame. Once in a while he will pivot the camera to follow them, but the camera remains stationary. He uses this method in the powerful scene depicting the punishment of two of the priest's children. They enter a room at the end of the hall, closing the door behind them. The camera rests, statically, and gradually we hear the sounds of whipping issuing from behind it. It has been said of Haneke that he likes to test the modern audience and its desire to witness violence acts; therefore, he deprives them of that pleasure. Here, denying us access makes the punishment even more shaming. The rest of the missing scenes work in a different way, because we are able to imagine any number of people executing the crimes. And forcing the audience to use their imagination in this way, makes even us possible perpetrators.

In another scene, the school teacher (Christian Friedel) witnesses one of these children, balancing tenuously on the railing of a bridge. The teacher anxiously yells for him to come down; the child claims, inscrutably, that he gave God a chance to punish him, but God didn't take the chance, so he must want him to live. Likening his parents, the highest authority he knows, to God, creates the oppressive state of ignominy leading to his and the other childrens' sociopathy. Throughout the film, we bear witness to the adults' hypocrisy. Their adulterous and incestuous crimes go unpunished, while the children are tied to their beds to prevent masturbation, or beaten for staying out too late (although what we are meant to assume they are doing might be deserving of such a punishment, or worse).

In another scene, the school teacher (Christian Friedel) witnesses one of these children, balancing tenuously on the railing of a bridge. The teacher anxiously yells for him to come down; the child claims, inscrutably, that he gave God a chance to punish him, but God didn't take the chance, so he must want him to live. Likening his parents, the highest authority he knows, to God, creates the oppressive state of ignominy leading to his and the other childrens' sociopathy. Throughout the film, we bear witness to the adults' hypocrisy. Their adulterous and incestuous crimes go unpunished, while the children are tied to their beds to prevent masturbation, or beaten for staying out too late (although what we are meant to assume they are doing might be deserving of such a punishment, or worse).Did the children commit these crimes? Probably, yes. But Haneke, as he has done in the past, implicates everyone in these violent occurrences. Directly or indirectly, nearly everyone is responsible.

(image the first)

(image the second)

(image the third)

Labels:

2009,

drama,

Michael Haneke,

new release,

Palm D'or

Saturday, March 6, 2010

Les Diaboliques

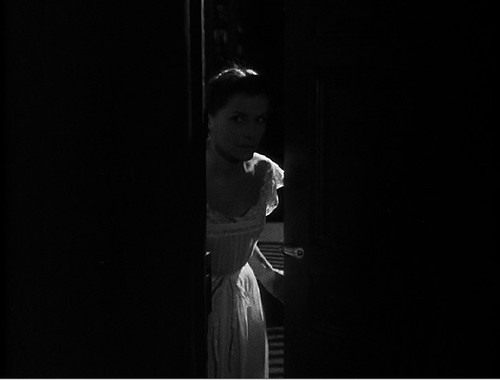

If this movie seems somewhat dated now, it's only because it set the precedent for movies of its kind. It is a well-known influence on Psycho, for instance. I think it probably operates in a different way now than when it was first released. Any modern viewer who is even partially literate in the thriller genre will have a pretty good idea of how it might turn out. In that case, the thrills lie in the movement from point A to the inevitable point B. And you can revel in the filmmaking that takes you there. In Les Diabolique, Michel Delassalle's (Paul Meurisse) wife, Christina (Vera Clouzot) and mistress, Nicole (Simone Signoret) conspire to kill him. This plan is already in place at the outset of the film; his murder takes place in the first 45 minutes or so. From the on, the narrative is driven by Christina's contrition, fear and consequential hysteria.

The scene above foreshadows the coming events, and demonstrates the power relationships pretty nicely. In contrast to Michel and Nicole, Christina is brittle and weak, with a heart condition to accompany her emotional fragility. Her already diminutive appearance is accentuated by the school girl braids that adorn her head throughout the film. She is dominated by all the characters around her, including Nicole, who pushes her to carry through with their homicidal plans.

Close ups! Reaction shots!

Due to the nature of Michel's death, there is an understandable focus on liquids. The opening credits take place over an abstract sort of background that is later revealed to be the swimming pool in the school yard. Bathtubs and pools are filled and emptied, as are pharmaceutically altered wine bottles, like the one that leads to Michel's immobilization. At one point, Plantiveau (Jean Brochard), the caretaker compares a full bottle to the soul, which, as we reflect on the doctored wine from a few scenes earlier, adds a new level to Christina's religious guilt about her actions. I also like to think there's some Stygian metaphor here, particularly in the many images of the murky pool water. The image above is very reaper-esque to me. There is also a sense of fatalism as Christina waits for the caretaker to discover the body once he has drained the pool. Meanwhile, the boys behind her are reciting their language lesson, conjugating the verb "to find."

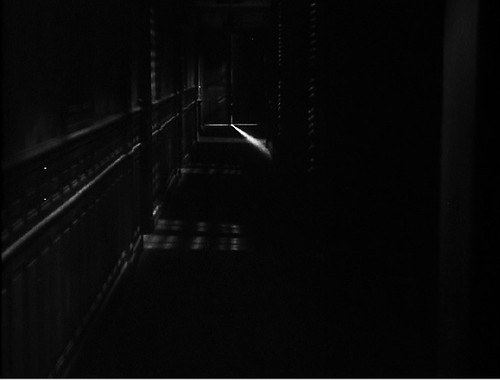

The best part of the film is the denouement, of course. Where the film, which has been relatively fast paced up until this point, slows down dramatically. The sense of space becomes drastically different, as well. The hallways that the frightened Christina stumbles through seem endless and labyrinthine. The way the sequence is edited, it is nearly impossible to ascertain where Christine is in the house and whether she is the one following or the one being followed.

(Spoilers) Another thing I like about this ending is the way in which it recalls an earlier moment in the film where Christina notes that she her only wish is that Michel would be aware that she had killed him. In a similar fashion, Christina will never know exactly how her own death came about. She is positive that she has committed murder, and that she is a murderer. Therefore, it is true. It doesn't matter that Michel was never actually dead. She still intended to kill him, and took all the necessary steps to ensure that it happened. In the end, they are all sinners; they are all devils.

Labels:

1954,

Criterion,

Henri-Georges Clouzot,

horror,

Les Diaboliques,

suspense,

thriller

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)