I still love you, but I've kept you hanging on. I sincerely apologize. It only took me about two weeks to get this post up.

The Man Who Wasn't There is the Coens' version of noir. It follows in the tradition of noirs like Quicksand (1950), in which average people, usually in some kind of financial struggle, become involved in crimes that quickly spin out of their control, becoming more and more serious. Billy Bob Thorton plays Ed Crane, a stony, laconic barber who resorts to blackmail to invest in a get-rich-quick scheme (dry-cleaning). This blackmail leads to manslaughter and spirals downward from there.

The Man Who Wasn't There is the Coens' version of noir. It follows in the tradition of noirs like Quicksand (1950), in which average people, usually in some kind of financial struggle, become involved in crimes that quickly spin out of their control, becoming more and more serious. Billy Bob Thorton plays Ed Crane, a stony, laconic barber who resorts to blackmail to invest in a get-rich-quick scheme (dry-cleaning). This blackmail leads to manslaughter and spirals downward from there.

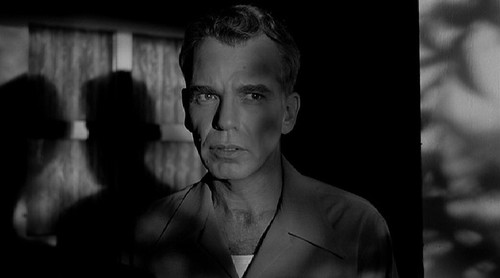

Ed's wife, Doris (Frances McDormand) is cheating on him with her boss, Big Dave (James Gandolfini). Though he suspects this, Ed's clandestine revenge is blackmail, rather than confrontation. His actions and his general countenance raise a lot of questions about what masculinity is. Several times throughout this film, Ed finds himself faced with the question: what kind of man are you? Rather than confronting Dave, he secretly blackmails him instead. In contrast, when seeking answers, Big Dave commits physical assault. Though we never see this action, it is implied that Dave beat his victim to death. Although Crane is considered by Dave to be a lesser man, it his emasculation by his wife that prompts him to go on this voyage in the first place. However, being Ed Crane, an invisible man, he is incapable of the confrontation that would allow him to reclaim his masculinity. Traditionally in Hollywood, being a man of few words is preferable to being as incessant a speaker as Big Dave is. Actions are supposed to speak louder than words, but Ed does not seem to utilize action or speech to the world outside of the audience, who he reaches through voiceovers. Thus, in Ed's Case, the question of masculinity is related to the question of ontological existence. Especially in a filmed world, who is more real? Those who speak, or those who don't?

As the title might suggest, the film raises some ontological questions as well, questions of identity. Ed is a sharp contrast to all the other men around him. As a barber, he is the sounding board to their empty chatter. This film is filled with talkers--Ed's brother in law, Frank (Michael Badalucco) , the lawyer, Freddy Riedenschneider (Tony Shaloub), the shady salesmen with an outrageous toupee (Jon Polito). Ed never lets a superfluous word slip out. Is this what makes him "the man who wasn't there?" The audience hears his voice; we know that he is complete. To us, it is the talkers that seem empty; their babble is not a sign that they have any real substance. Crane's silence as well as Thorton's excellent control of his features and the frequent shots of his face, reveal him more fully. Since we have access to his inner monologue as well, we respect his words when he does decide to speak. From the viewer's perspective, by the end, it almost seems as if it is the other characters who were never there.

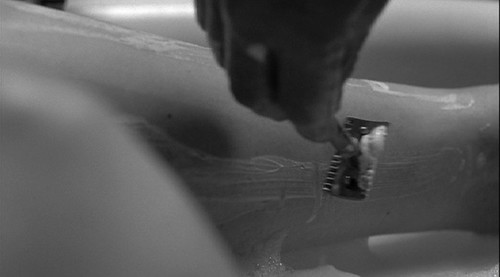

Aside from the state of being, there are several other pervasive themes in this film. These are hair and alien abduction. Naturally, Ed Crane's profession is an aggregated source of metaphor in the film. As Crane's problems become more severe, he becomes preoccupied with the idea of hair. It is a dead part of us that we cut away; it never stops growing, yet it seems to be without a source. A close-up shot as he shaves his wife's legs is echoed in the final scene, when he is shaved in preparation for the placement of electrodes on his body. (And he ends up seated in a chair that is oddly similar to his barber's char). Hair seems to operate as a metaphor for existence, death and rebirth in an apathetic universe. Like hair, life continues on, seemingly without a reason, when all reasons are gone. When we have no more use for it, we cut it off and throw it away.

The topic of alien abduction also pops up several times. Big Dave's wife uses an abduction fantasy (we can only assume it's a fantasy) to deflect the problems in her life, such as her husband's loss of interest in her. She also suspects that the aliens are behind her husband's murder. Later, a flying saucer is pictured on the front of a paper Ed reads. Soon, the imagery begins to take on an otherworldly tone. In the still above, Freddy Riedenschneider stands in a beam of light that is reminiscent of a prototypical flying saucer beam.

Here, I love the recurring image of the saucer in its various manifestations:

In the same vein, when his narrative flies out of his control, Ed begins to see visions of flying saucers. I think alien abduction is a really interesting substitution for religion, if not an outright mockery of it. When confronted with a fatalistic universe, where most would seek refuge in religious doctrine, Crane seeks a similar explanation for his loss of control. Mostly what this demonstrates is that noir, like all genres, has its own doctrine; once certain steps have been taken, you have to ride the train all the way to the end, as they say in Double Indemnity.

Of course, Crane is duly punished for his actions. Hair today, gone tomorrow.

hair taday, gahn tamarrrah

ReplyDelete